None On Record

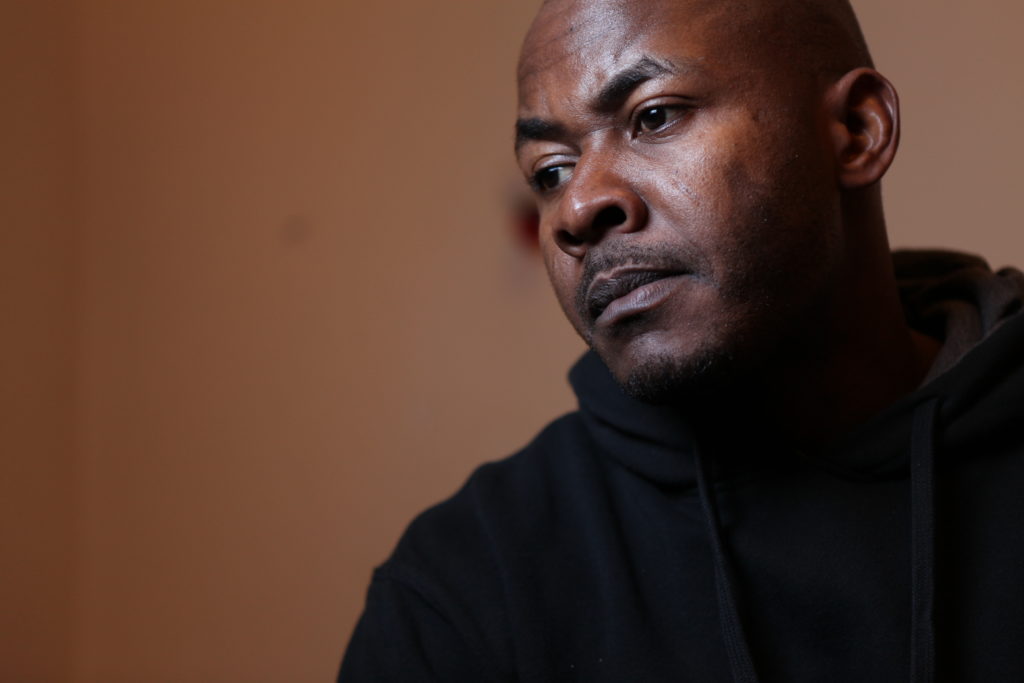

Interview by Mariam Armisen. Photos by None on Record

None on Record is a digital media project that collects the stories of LGBTI Africans. Their motto is “a story is the shortest distance between two people.” Q-zine talked with None on Record founder Selly Thiam in New York.

How did None On Record get started?

In 2004, Fanny Ann Eddy, a prominent LGBTI activist from Sierra Leone, was murdered in her office. I wanted to do some kind of creative work to honor her memory by telling some of the stories of LGBTI Africans. In 2006 I drove to Toronto to do an audio interview with a Sierra Leonean lesbian living in Canada. The interview was broadcast on National Public Radio in Chicago, and after that I wanted to keep going. I wanted to meet more LGBTI Africans, so I started by traveling around the United States and Canada talking to other exiles and then began collecting stories in South Africa. After my South Africa trip, I began to focus on other countries in Africa. I wanted to make sure that None on Record was a global project that collected stories about LGBTI Africans from everywhere in the world. To date we have collected over 250 stories, and our archive is still growing.

It’s very refreshing for me to see that, except for the graphic designer, None on Record has a female-identified staff. Is this a deliberate decision?

I am not sure it was deliberate in the beginning. I just started working with the people who wanted to work with me. But as None on Record grew as a project and then as an organization, we have been careful about making sure that our staff reflects the communities we work in and the stories we collect. And as a woman who has worked in several media organizations that had very few women making decisions, and even fewer people of color, I am committed to passing on the skills that were taught to me to other women and people of color. It is part of the mission of our organization and influences every project we take on.

The media democracy movement is mostly white and male-dominated. What have been the reactions when None on Record’s staff walks into a room for a project?

It depends on what room we are walking into. When we interview people in the African LGBTI community, the reception is usually warm. People are excited to participate. The most pushback we have received about the work we do is from some journalists or producers who think our work is strictly about advocacy. Advocacy has become a dirty word in journalism. It is often said that advocates have an agenda and journalists should not. But when you come from a community where you have not been able to tell your own story or where so few of us have been let in the room to do so, you don’t believe the press is objective. It is easy to point fingers and discredit work that does not fit into the mainstream narrative. But if we worried about that we wouldn’t have gotten this far.

Digital media isn’t a big part of the LGBT movement in Africa yet. How do you overcome skepticism?

I don’t think we encounter skepticism. It’s more that people don’t see right away how digital media can be used as a powerful tool for social change within the African LGBTI movement. Digital media is all about the dissemination of information, and the way None on Record shares information is through stories. We believe that a story can transform people’s perspectives and ultimately their lives. When we show people exactly what we do, and why, it becomes easy for them to see how digital media can be used in their movements. People catch on to good new ideas very fast.

How do you navigate between the need to preserve anonymity and the need to create visual memories of LGBT Africans?

We have asked ourselves this question many times. When None on Record first started, we created a process where people could decide for themselves how they wanted to participate. If someone wanted to share their story, they would decide how it was distributed – either with their name and photo online, on radio or television, or they could share their story anonymously and it would be included in the archive. We offered many ways for people to be involved.

As the way people communicate has shifted over the years and the struggle for LGBTI equality has become increasingly visible on the African continent, more people are speaking out and attaching their names and faces to their stories and experiences. We have also shifted the way None on Record tells stories. We started in audio/radio, moved to photography with audio and now also have video portraits. In the beginning most people were uncomfortable with a photograph being taken, but now people are usually okay with video documentaries about their lives. It doesn’t mean the same level of risk isn’t there. In fact, as visibility has grown, so have the risks in many ways. But people are speaking out more now than ever, and are doing so increasingly on digital platforms.

Tell me about your most memorable project. What made it special?

That’s a tough one, because I love all of them. I love the process of making media and the people we meet. It is one of the most beautiful experiences you can imagine. A very human experience. So when I say that I have enjoyed all of them, but maybe for different reasons, I am just being honest.

How do you choose a project?

Often a project chooses us. For one of our most recent projects, Seeking Asylum, we were invited to Spain to present at a museum there. We had never collected in Europe before, so I wanted to take the opportunity to explore the African LGBTI experience there. The African LGBTI community is very vibrant in Europe

Then, as we were preparing to travel to Spain, a research study was released about Europe’s treatment of LGBTI asylum seekers. This focused our attention on collecting stories about asylum seekers and their challenges. We decided to do the production in the UK and produced a four-part series about African LGBTI asylum seekers from Uganda, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe.

Another recent project was a documentary we shot in East Africa. We were able to travel to all five countries in East Africa interviewing LGBTI activists.

Both of those projects have been amazing experiences for our production team. Now we are working on a new series that springs from stories we came across in those last two shoots.

Briefly walk us through the production of one interview. How many weeks or months is it before the final product is published? How many people are involved?

It depends on the media format. Producing audio and photo projects can have a faster turnaround time, depending on the type of documentary we are doing. Video tends to take a bit longer. But basically, someone on the team will pitch a story, and if everyone likes it, thinks it is a solid idea and that it fits our criteria, we decide on the best media format to tell the story and then go to work producing it. A team can be as small as one person who interviews, edits, and then publishes or as large as a team of six with assistant producers, director, videographer and editors. Projects can take anywhere from a few weeks to a whole year.

NOR recently opened its first office on the continent in Kenya. Tell me more about it. Why Kenya?

We always wanted to have a home base in Africa. We were mostly working out of New York, but with producers who worked and lived in South Africa, Senegal and Kenya. After I traveled to Kenya to do a digital audio training with LGBTI activists at the Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya (GALCK), several of the participants wanted to keep going with the work. That is when I began to think about bringing the project to Kenya permanently and involving activists on the ground in the founding and creation of the office. Now None on Record staff can work with LGBTI African communities throughout the region.

How is 2013 shaping up?

We are growing. We are looking forward to working with more LGBTI groups in Africa and developing the skills and reach of the staff in the organization. And we’ll soon be getting started on a production that tells stories from LGBTI Africa in some new and exciting ways. I look forward to coming back and telling you more about this project as it moves forward.