Family And The See-saw Of Coming Out

By Uchenna Walter Ude

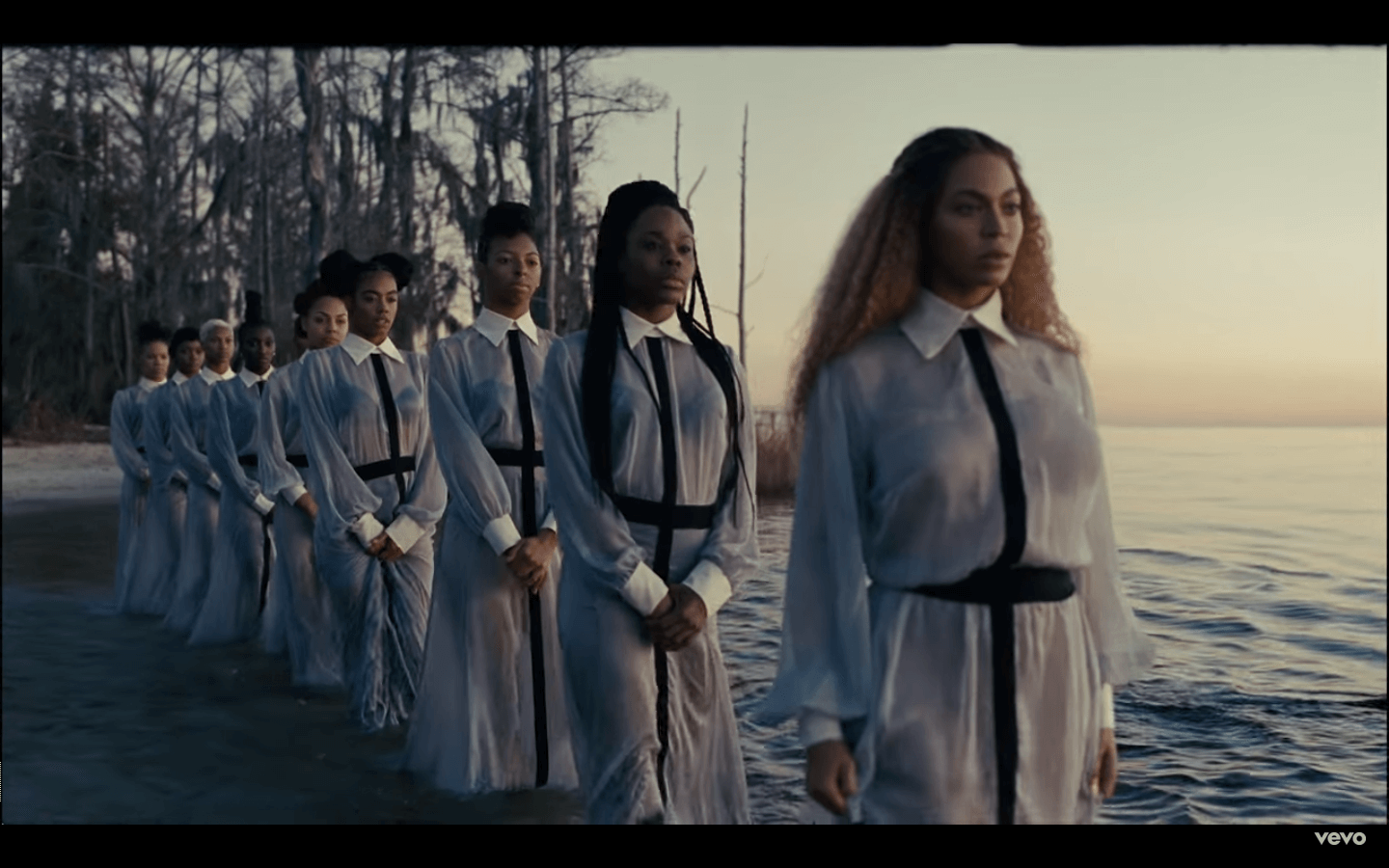

Illustrations by Aisha Shillingford

Coming out can be an incredibly freeing experience for some of us as we are liberated to finally openly identify as who we are. Freed from all those expectations that are placed on our lives by family and friends; the lies we tell to thwart suspicion; the silences we respond with to situations that demonize our identities; the damaging relationships we endure because they come with the territory of being in the closet; the fears we live with over one day being found out; living as ourselves secretively.

And for many queer people, this freedom is beautiful. It makes us better people, because we can only be our best selves when we no longer have to hide who we are. It puts us in more honest relationships and creates an environment around us where we can be compasses pointing to each other’s humanity and away from prejudice. Yet for some people, coming out is bittersweet. It’s a combination of some of these beautiful experiences with some of the more trying ones. And, for other queer people still, coming out is just the beginning of another hurdle they have to conquer. My coming out was bittersweet.

I came out to my mother – and by so doing, to my family – in September 2018. As someone who’d only ever cared about how my life affected my immediate family, coming out to them was all I ever cared about. And when I finally came out, I refused to be held back by anything else. I made myself as free as I could be under the circumstances of the society I live in, speaking out, using my life to try to normalize my reality as a gay man…

And constantly locking wills with a mother who has refused to accept the truth of who I am.

I used to tell close friends that I’d always believed that should I ever come out, my mother would be the one to support me and stand by me because of the closeness I shared with her. Whereas my father, who raised me and my brothers with a “do not spare the rod” mentality, would probably disown me.

When I came out, the reverse happened.

I realized that the older my father got, the less intractable he became. And so, when he learned about my sexuality, his reaction, after the initial wave of disappointment, was to struggle with acceptance while wishing and praying for a son that would stop being gay. In his private moments, I’d overhear him pray for God to “cure” me, and then emerge to ask me questions about my welfare, my struggles, my past. The day I told him about how lonely it was for me as a child who had started to realize how different he was, he broke down in tears, saying in anguish to me: “How could I be your father and not know?”

My father would talk to me about getting married, saying things like, “Are you sure you are gay? What if you’re really bisexual? That way, you can still get a wife…”

But he would also ponder things with me like, “Are you happy? Does this make you happy? Do you have other people in your life who know, who support you?”

He would express his mortification over how he should respond when relatives ask him about why it was taking me long to get married, and his dread should my homosexuality ever be something that’d be publicly known by other family members.

And he would also listen whenever I talked about gay rights in Nigeria and the advocacy I am involved in, always responding with some encouragement here and a word of prayer there.

My father didn’t know any better, but the reality of a homosexual son was making him want to know, to understand, to accept.

My mother, on the other hand, was a different story.

She doubled down on her homophobia, so wrapped up in her religiosity that she was sure that there was no way I could have a good life as long as I claimed to be gay. And that is what makes my continuing estrangement from her very sad: the fact that I can see that she loves me but loves me so wrong.

In the years since I came out to her, we have alternated between fighting and not speaking to each other. In those rare times when we manage to talk on the phone without any outbursts of anger, the exchange is usually wooden and joyless, or tense and awkward. I keep waiting for her to want to know, to ask me to tell her about me, about how I got here – and all I get is a mother who stays triggered by what she believes is my willful disregard for the will of God in my life.

During a homecoming in 2019, my parents called a pastor to pray for the family. The man of God was supposed to pray for the house we had just moved into, pray for the endeavours of everybody in the family – and pray for me.

“You see, Brother Emeka,” my mother said as we were all seated in the living room with the somber expressions of people about to go into the serious business of prayer, “there is something I’m asking God for my son. I have been asking God to deliver my son from this particular will of Satan for months now. I need you to help me ask God to loosen him from this shackle of the enemy.”

For a moment, the pastor looked at my mother, undoubtedly expecting her to go ahead and elaborate, to tell him what satanic shackle it was he was supposed to pray for to be broken. He looked at her and she looked back at him, not saying a thing.

And I chuckled inwardly, wondering if I should give in to the sudden temptation to say to the pastor: “Oh sir, what my mother means is that she wants you to pray for me to stop being homosexual.”

But I didn’t.

And the pastor prayed.

And then we went back to our lives, while this incident became yet another knot in the growing tensions between a son who just wants to live and a mother who won’t accept that.

My coming out is beautiful, and I sometimes must remind myself to constantly guard against moments that make me lose myself. In this practice, I am able to choose my family again, both from the one I am related to and the one I can relate to.

The past few years have been a journey of freedoms and frustrations for me. I am always grateful for the circumstances in my life that have made it relatively easy for me to live out and proud of who I am. That has made it so that I still enjoy close, loving relationships with people in my life who I am now out to and are accepting of me. And it means that the first time I typed something that was very openly gay for an update on Facebook, I was able to click “Post,” and after a few heart-pounding seconds, realized that I was okay, that it was now okay for me to be me on social media. I am now more keen on identifying and relating with people in my community, unencumbered by internal battles of my identity, freely relating to these people based on shared trauma and individual journeys to self-acceptance.

I came out, and suddenly, there was an end to everything that made me scared and doubtful and loathing about who I am.

My coming out became a new beginning, a time to reassert myself and say to people like my mother, “Yes, I’m gay and it’s perfectly fine that I am gay.” When new doubts about outcomes in my life, as a result of my mother’s beliefs creep up, I stop and tell myself: “No, you did not experience that failure because you’re gay. Your mother may believe so, but you know better.” Or, “you are not cursed for being homosexual, no matter what your mother says.”

My coming out is beautiful, and I sometimes must remind myself to constantly guard against moments that make me lose myself. In this practice, I am able to choose my family again, both from the one I am related to and the one I can relate to.

It can be exhausting, but what then is the alternative?