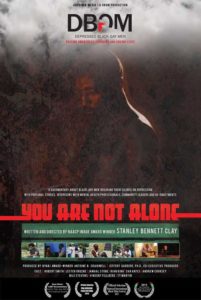

You Are Not Alone

An interview of Filmmaker Antoine B. Craigwell by Cases Rebelles

In 2012 Antoine B. Craigwell produced the documentary “You Are Not Alone”, bringing focus on and raising an alarm to psychological distress among gay black men. Based on powerful testimonies of men suffering from depression or having dealt with depression, and interviews with experts in mental health, the film expresses a suffering endured in silence, invisible to their families, as well as in the gay community, and the enabling factors that can lead to risky behavior (drugs, unsafe sex) and even suicide.

There is urgency, says the documentary, to talk about, to break the isolation – to love oneself and to share this love with family and the community – to fight homophobia and all the violence it causes. Originally from Guyana, now based in New York, Antoine B. Craigwell is a journalist, the President and CEO of the organization DBGM (Depressed Black Gay Men – an organization providing essential, daily support and prevention services to men of all ages and their families, specifically their mothers). Here is an interview with a bold activist, in which he discusses the genesis of the project “You are not alone”, DBGM work, and his activism back in Guyana.

Where were you born, where did you grow up?

I was born in New Amsterdam, in the county of Berbice, in Guyana. It used to be a part of the Dutch colonies. And the country I was born in is the location of one of the most famous black slave revolts led in 1763 by a slave by the name of Kofi (Cufy). According to historians, Kofi overthrew several plantations owners, the white Dutch plantation owners. By that time in 1763, the Dutch gave Berbice county to the British. So he overthrew a lot of white plantation owners and held a lot of the plantations together – they actually survived as a commune, as a cooperative, as villages for 2 to 3 years before the British were able to send reinforcements and he was betrayed by another slave who enabled the British to capture and kill him. That’s a brief history of the county where I was born.

I came to the US as an adult. I lived most of my life in Guyana

How did the idea of the film come to you?

I’m originally a journalist – that’s where my specialty is – but I came across the idea of doing a book about depressed black gay men after hearing stories from other black gay men about where they were in their lives and how they felt stuck and unable to move forward, and not quite knowing why it is they were unable to move forward with their lives. After hearing the stories and having done some study in psychology – because I have double degrees in journalism and psychology – I recognized that under the surface, many of these men were actually dealing with depression. And when I started to investigate and ask questions, some of them knew they were depressed and they had been seeing therapists, others knew that they had dealt with depression and had seen therapists but they no longer saw therapists, and there were others who were not aware that they were dealing with depression although their behaviors, their attitudes, their actions were a reflection of people who have dealt with, were dealing with depression or having experienced depression.

So I started to write a book, which I’m still trying to find a publisher – or an agent to help me find a publisher. I interviewed 40 black gay men from United States, the Caribbean and Africa, mental health professionals, and religious leaders including Christians and Islamic leaders. And because I couldn’t find a publisher I decided that since people respond more to visual images, then I should do a documentary. So I asked some of the guys I interviewed for the book if they’d be willing to sit in front of a camera and tell their stories, and they were like, “Yeah, certainly”. So we decided to film a lot of the interviews, and then we hired a director who wrote a script based on the interviews, and he did the casting and the sets and the studios and all that kind of stuff, and we reenacted some of the stories that were told in the interviews.

One has to go back and look at the underlying psycho-social or socio-economic or socio-cultural factors in a person’s life to understand what’s going on, what contributed to their descent into depression. And depression is just one step away from someone wanting to commit suicide. And so the ultimate objective is to prevent a black gay man from committing suicide at all cost.

Out of the book at least 5 distinct themes emerged: 1) sexual identity, sexual orientation and gender expression; 2) sexual abuse and trauma; 3) HIV and dealing with HIV; 4) the effect of religion on someone’s sexuality and homophobia and bigotry that religion brings causing someone to descend into depression; 5) what it was like for someone who’s growing old, as an older black gay man, to live in today’s youth obsessed society and deal with the loneliness, the abandonment and health issues and reduced income and shrunken network of friends and, possibly, the estrangement from family.

An important point is that the film talks about and directly to multi-generations…

We always talk about the upcoming generation, since the dawn of time, we look at the next generation that doesn’t know anything – and as a matter of fact the generations before us probably thought the same thing about us and probably still do. What is important I think for the younger generation to understand is that if they live long now, that these are some of the issues that they will be faced with, as they get older, and for those who are not quite as old, these are also some issues that will be fast approaching.

Our message really to the younger generations is very simple, if you feel that you’re going through some issues and you have issues that you’re dealing with, don’t keep them inside, talk to someone, find someone you trust and talk to that person – because the person will realize that he is not alone, that he is not the only person experiencing this. We always tell ourselves no one can understand what we’re going through, no one can understand what is happening to us, but the actual fact we will discover if we talk about it is that there are a whole lot of people around us who had similar experiences, and this is what the film is intending to do.

How did the interviewees receive the film?

They were all very happy, they were glad with the way that it turned out, they felt really good, they felt very proud when it was premiered in November 2013 here in NY at a gala that my organization had – so they were able to see it and a lot of people were proud of it, they were happy to see what they said was captured.

One of the guys in the documentary passed away before it could be finished, he died in June 2011, he was interviewed in about January 2011 and he died in June 2011, so he did not get a chance to see the film.

What is the story of DBGM?

DBGM was founded as an extension of the documentary to raise awareness around depressed black gay men; it was part of the process. This year alone, the organization is about to launch 2 new programs here in NY City: one is a support group for mothers whose sons have committed suicide and, the second one is a support group for young black gay men whose mothers have not accepted them for who they are. One of the things we discovered, not limited to the research for the documentary, the book or the interviews, is that we recognize that our mothers are the catalyst – our mothers are the ones who help us, help our men to form their masculinity, determine their manhood and more important their sexual identity. So we focus now on mothers. Helping them to heal so that they don’t feel that they are to be blamed, that they are failures, not worthy of being mothers, so that they can heal and bring their family back together – and that they would be able to reach out to other mothers who may have sons that are gay but are still not accepting those sons

What are your connections with Caribbean organizations?

I am connected to SASOD, which is a LGBT organization in Guyana. The film was shown as part of SASOD film festival in Georgetown last June and, in August, the film was one of the selections that the government of Guyana submitted to CariFest, which took place in Suriname. Carifest is a Caribbean arts festival.

I am connected to a number of different Caribbean organizations here in United States; just last Friday night together with Caribbean Alliance Equality, which is an organization in Philadelphia, we had a screening of the documentary.

How was the film received in Guyana?

It was very well received – I skyped-in for the screening followed by a discussion at the SASOD’s Film Festival; there were quite a number of people who attended. A catholic bishop of Georgetown also attended the screening and saw the film and after the film while I was still on skype, I could hear what he was saying and his responses to questions from the audience. After the discussion was over he and I had a conversation over Skype and I asked him why he bothered to come, to participate in this, and he said that as a new bishop in Georgetown he felt it was necessary to understand the different dynamics, the different groups that exist and he wanted to understand what is going on with the black gay community, or the LGBT community in Guyana. So he accepted the invitation to be part of a panel after the film was shown in Guyana, so that he can see the film and discuss it – and I think that maybe that was a significant step forward.