Abdellah Taïa: Writing and Fighting for Arab-Muslim Gays

By Gibson Ncube

Of the monotheist religions, Islam has long been lavished with praise as a religion that shows great acceptance of human sexuality. In Islam, sexuality, as long as it is between a man and woman within the confines of marriage, sexuality has no negative connotations and is celebrated. The same cannot be said of homosexuality. The Qur’an is explicit in its condemnation of homosexuality and no ambiguities exist with which to theologically tolerate homosexuals. Nevertheless, homosexuality has historically been tolerated in many Arab-Muslim societies, albeit remaining mainly in the realm of the unspoken and the taboo.

This is the context in which the openly gay Moroccan writer Abdellah Taïa finds himself. Born in Rabat in 1973 (Morocco), Taïa has published several novels in French, four of which centre on the difficulties of being gay in an Arab-Muslim society with entrenched cultural practises and piety. His official coming out was marked by a highly publicised interview in the Moroccan magazine Tel Quel in 2006. This interview triggered profound seismic socio-cultural and political debate in Morocco centring on homosexuality.

Two possible explanations can be proposed as to why and how Taïa writes as daringly as he does. To begin with, he is based in Paris, and this real and perspectival distance from his home country offers the necessary detachment to generate a more critical evaluation of what happens in his country of origin.

In addition, Taïa’s indelible media presence has contributed to his identity not just as a transgressive writer defending the rights of gays but also as a noted socio-political commentator. He rightly points out that “as a Moroccan, an Arab, a Muslim, an African, and a writer, I know that when you have the opportunity to speak you have to do it. There is no other choice. I am also very happy to speak about things that other people say don’t exist. They say homosexuality doesn’t exist in the Arab world, but I am here to prove the opposite and speak about it from the interior.”

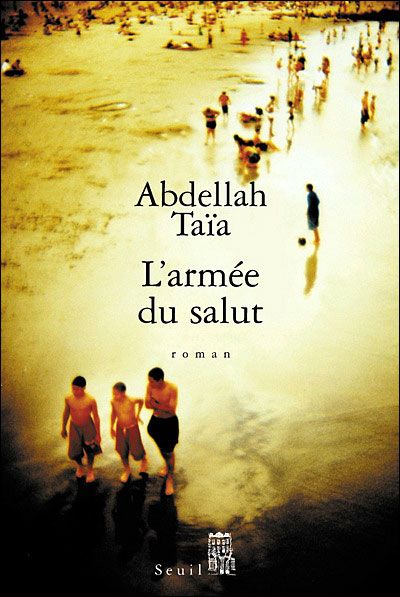

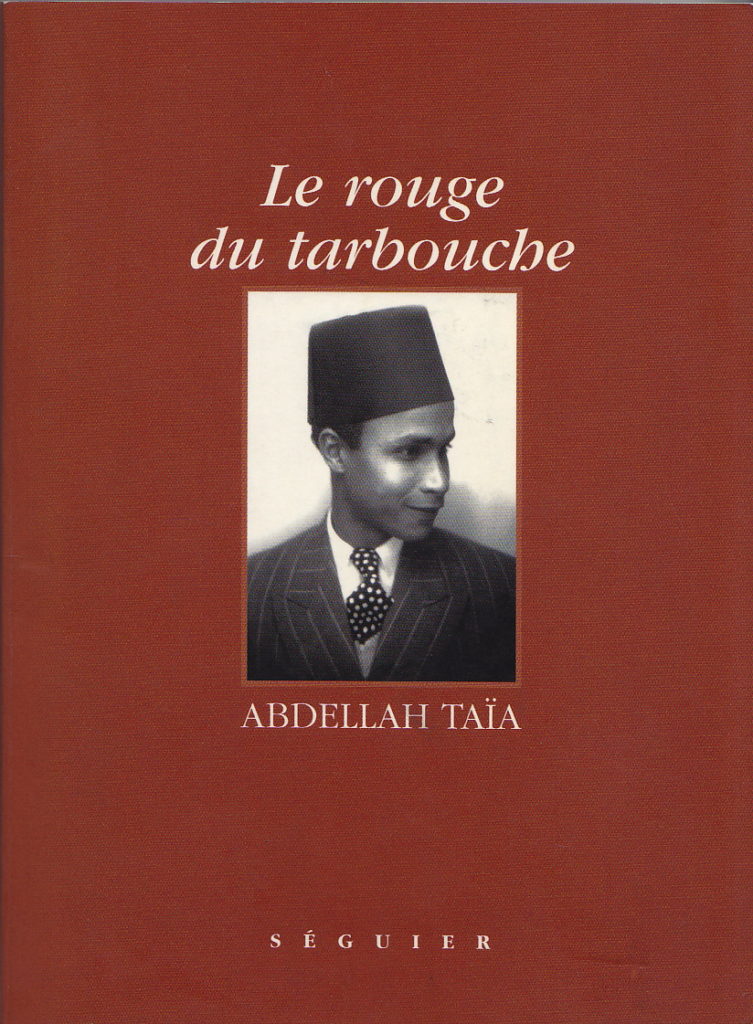

In line with this manifesto, Taïa’s novels offer an overt treatment of the theme of homosexuality in an Arab-Muslim milieu. In Mon Maroc (2000), Le rouge du tarbouche (2004), L’armée du salut (2006) and Une mélancolie arabe (2008), he uses interior monologue fragments of his youth fused with philosophical anecdotes to raise the most challenging questions about the condition of gays in the Arab-Muslim world.

Brought up in a family that refuses to recognise his homosexuality and insists he be a “normal” young man, the protagonist-narrator in these texts undergoes an agonising and protracted process of self-actualisation. From a timid and lacklustre adolescent, he transforms into a fearless intellectual who confidently explores his so-called “deviant” sexuality.

Suffocating in a claustrophobic family and society, the protagonist, like the author himself, leaves for Europe (first Geneva and then Paris), which, in spite of the coldness of both its weather and inhabitants, offers him a place in which he can embrace and freely live his sexuality.

Writing offers him a catharsis through which to reconcile himself to his past and recover from the hostility he experienced in his family and home country. In Homosexuality Explained to My Mother (2009), an open letter to his family, and to his mother in particular, Taïa explains that he writes about his homosexuality so that others will finally consider gays as “human beings worthy of receiving explanations.” Far from being scandalous for the sake of being scandalous, Taïa clarifies that his writing is both a gift and, as his attempt to give voice to the marginalised and voiceless gay Muslims, a duty.

Abdellah Taïa’s novels thus strive to engage constructively with his country of origin, not just shock it. He sees the decidely mixed reactions to his novels as a first step in opening the necessary dialogue about (and with) those who have been ostracised because of their sexual orientation.

Although some critics accuse Taïa of writing to satsify Western readers, there is no doubt that his novels have gone a long way to giving a voice to gay people in Arab-Muslim societies. These pioneering novels meditate aslant, catechise, and create a new grammar and language of homosexuality for the Muslim world. For both Muslim and non-Muslim readers, they open fresh perspectives on “marginal” sexualities and sexual identities in contemporary Arab-Muslim cultures.

In an article in the gay and lesbian magazine Têtu (May 2012), Cédric Douzant laments that, a year and a half after the Arab spring, it is still winter for queer Arab-Muslims. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that, in the context of the Arab spring, the writings of Abdellah Taïa and other emerging queer Arab artists have the potential to provoke a reconceptualised consideration of Islam. They call attention to its relevance and its adaptability to changing times, particularly concerning the condition and rights of gays.