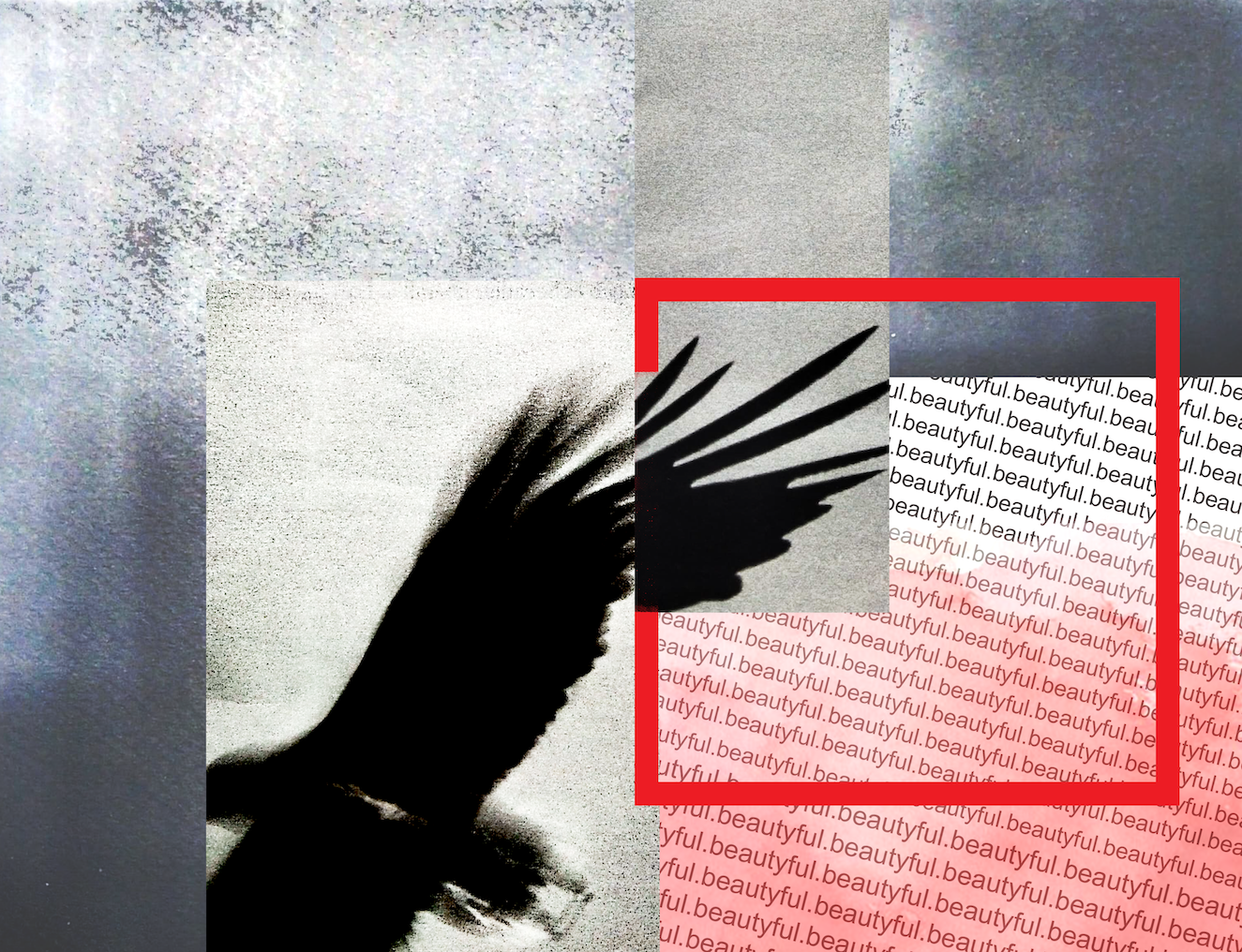

And the caged bird will sing beyond death

A review of The Death of Vivek Oji by Wanini Kimemiah. Illustration by Rosie Olang

Tragedy narratives are some of the most complex and compelling narratives in fiction. The premise is simple enough; the story begins with a great horror, and the rest of the book is a picture of the events before or after tragedy struck. With Akwaeke Emezi’s third novel, The Death of Vivek Oji, the tragedy is already in the name. However, the greatest tragedy in this story is not Vivek’s death, it is the unfortunate, soul crushing reality of their life. The book is a bold assertion, challenging the consuming despair we are told is our life and destiny as queer African people reeling from the many violences of being colonized people. There is death, yes, there is relentless terror; but there is also joy. There is also life.

Vivek is a bird ready to fly away; brilliant and bright and wonderous. They are born to a grieving family and the circumstances of their birth further complicate this grief. It is this same grief and miasma of death that follows Vivek throughout his brief life and obscures the truth about who he really is to his family.

“Picture: a house thrown into wailing the day he left it, restored to the way it was when he entered. Picture: his body wrapped. Picture: his father shattered, his mother gone mad. A dead foot with a deflated starfish spilled over its curve, the beginning and end of everything.”

In The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson writes: “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.” The absolute reality of death that Vivek’s family lives under makes it impossible for any of them to allow themselves or their children to dream. Mary’s miscarriages hardened her into a bitter and fanatical woman who couldn’t even love the one child she did have. Under her heavy hand and Ekene’s negligent parenting, Osita withered throughout his childhood into a joyless young man. A misery like that can sully any good thing into something perverse, which is what his filial affections for Vivek mutated into. The absolute reality of Vivek’s own household shrunk Kavita’s world to her only child. She vows to have no other children and devotes herself to raising him. And yet, her grief at having lost Ahunna keeps her from truly seeing her child.

Chika, even less. He is dismissive of the truth of Vivek from his birth and as he grows older, resorts to even sending him away to military school to “toughen him up”; to beat out the truth of him by thrusting him into a violently conformist hypermasculine environment. There’s something to be said here about how the worry of African fathers for their sons (some who are secretly daughters) can only be expressed through absolute violence. If they kill your spirit, nobody else can. Chika wields manhood like a weapon and he is not afraid to bludgeon Vivek with it. Ahunna lives on in Vivek, but he would much rather she die again than accept his only child.

Vivek persists despite the death and dysfunction that plagues them. When the option to leave their family behind and make a new life while studying abroad is no longer an option, they conjure up an existence for themselves out of thin air. In the face of death, Vivek does the brave thing that nobody in their family has attempted to do in decades; they choose life.

Vivek is a caged bird, but they have adorned their enclosure and adorned themself in magnificent splendor. In chapter 6, Vivek says: “Beautyful. I have no idea why that spelling was chosen, but I liked it because it kept beauty intact. It wasn’t swallowed, killed off with an ‘i’ to make a whole new word. It was solid; It was still there, so much of it that it couldn’t fit into a new word, so much fullness. You got a better sense of exactly what was causing that fullness. Beauty.”

The kinship and community they build with Juju, Elizabeth, Somto and Olunne is the balm that they need. They allowed them to spread their wings a little and shake the dust off their feathers. The girls allowed Vivek to dream, and dream she did. Osita on the other hand was completely unable to shake the baggage heaped on him by his family. He succumbed to it completely and it distorted who Vivek was to him. Osita watched Vivek change and free themself from the worst parts of the trauma passed on to them, and this terrified him. Why couldn’t they be content with their chains? Why couldn’t they accept the reality that there would never be any room for acceptance for the truth of them in their family or community as he had? Osita deeply resents that Vivek gave themself permission to exist, and not just exist, to defy categorization or simplicity or respectability. Vivek chose life and beauty where Osita was content with death and decay. It is this resentment, this rage that ultimately leads to Vivek’s untimely death.

Some may argue, and have argued that Emezi’s choice to depict an incestuous relationship between the cousins is for shock value and entirely gratuitous, but I disagree. They are not the first or last author to explore the idea of dysfunctional families and generational trauma using incestuous relationships. The relationship between the twins in Arundhati Roy’s God Of Small Things is alluded to being similarly inappropriate, and much like in that story, it proves to be incredibly damaging for both parties.

“Beautyful. I have no idea why that spelling was chosen, but I liked it because it kept beauty intact. It wasn’t swallowed, killed off with an ‘i’ to make a whole new word. It was solid; It was still there, so much of it that it couldn’t fit into a new word, so much fullness. You got a better sense of exactly what was causing that fullness. Beauty.”

It’s not comfortable, or easy to consider such possibilities when writing a story about queer people. Especially since as a result of the prevalent fundamentalist Christian propaganda, many people in Nigeria think of queer people and in particular transfeminine individuals and men as aggressive sexual predators on par with sexual abusers. But perhaps that is the point of this particular narrative. It is a very poisonous idea that causes countless queer people untold physical and psychological harm from the people around them. How much worse could it be to internalize these ideas? The two are obviously aware of how inappropriate their relationship is and they keep it a secret from their friends for the longest time.

I believe the narrative invites us to question the conditions that lead to a damaging and dangerous relationship as this one. The volatile combination of Vivek’s emotional distress and the idea that there were no other options or opportunities for love or intimacy for them proved ripe conditions for their relationship to begin. To me, this relationship is a sharp criticism of the hypocrisy of Nigerian society and attitudes towards queer people. You cannot poison a well and be angry when the water kills you. Undoubtedly, Vivek had come to a point where she no longer needed Osita in the desperate way she had, and I think that it is significant that mistakenly or not, Osita killed her for it.

Emezi makes a powerful statement by having Vivek honoured in death in a way she was not while alive. For many trans people, dying is just another continuation of the erasure they suffered in life. The deceased are buried in clothes they’d never wear, under names they no longer used and remain misremembered in the minds of their families. Kavita gave her child a send-off befitting their life. She made sure to dress them in the clothes she knew they loved, didn’t cut their hair much to the disgust of the rest of the family, and ensured that the headstone had the correct names for Vivek. It is a shame to die young, but sometimes in death, one can finally find the freedom life could not offer. What is death anyway but one half of the cycle of existence? From beyond the grave Vivek says:

“I was born and I died. I will come back. Somewhere you see, in the river of time, I am already alive.”

Vivek was a bird with clipped wings when she was alive, but in death she spread her wings and soared.